The 1892 Homestead strike in Pennsylvania and the ensuing bloody battle instigated by the steel plant's management remain a transformational moment in U.S. history, leaving scars that have never fully healed after five generations.

The skilled workers at the steel mills in Homestead, seven miles southeast of downtown Pittsburgh, were members of the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers who had bargained exceptionally good wages and work rules. Homestead's management, with millionaire Andrew Carnegie as owner, was determined to lower its costs of production by breaking the union.

Carnegie Steel Co. was making massive profits—a record $4.5 million just before the 1892 confrontation, which led Carnegie himself to exclaim, "Was there ever such a business!" But he and his chairman, Henry Frick, were furious workers had a voice with the union. "The mills have never been able to turn out the product they should, owing to being held back by the Amalgamated men," Frick complained to Carnegie.

Even more galling for them was that, as Pittsburghlabor historian Charles McCollester later wrote in The Point of Pittsburgh, "The skilled production workers at Homestead enjoyed wages significantly higher than at any other mill in the country."

So management acted.

First, as the union's three-year contract was coming to an end in 1892, the company demanded wage cuts for 325 employees, even though the workers had already taken large pay cuts three years before. During the contract negotiations, management didn't make proposals to negotiate. It issued ultimatums to the union. The local newspaper pointed out that "it was not so much a question of disagreement as to wages, but a design upon labor organization."

Carnegie and Frick made little effort to hide what they had in mind. Their company advertised widely for strikebreakers and built a 10-foot-high fence around the plant that was topped by barbed wire. Management was determined to provoke a strike.

Meanwhile, the workers organized the town on a military basis. They were "establishing pickets on eight-hour shifts, river patrols and a signaling system," according to McCollester.

Frick did what plenty of 19th-century businessmen did when they were battling unions. He hired the Pinkerton National Detective Agency, which was notorious for such activities as infiltrating its agents into unions and breaking strikes-and which at its height had a larger work force than the entire U.S. Army.

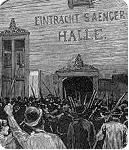

When Frick plotted to sneak in 300 Pinkerton agents on river barges before dawn on July 6, word spread across town as they were arriving and thousands of workers and their families rushed to the river to keep them out. Gunfire broke out between the men on the barge and the workers on land. In the mayhem that ensued, the Pinkertons surrendered and came ashore, where they were beaten and cursed by the angry workers.

At the end of the battle between the Pinkertons and nearly the entire town, seven workers and three Pinkertons were dead. Four days later, 8,500 National Guard forces were sent at the request of Frick to take control of the town and steel mill. After winning his victories, Frick announced, "Under no circumstances will we have any further dealing with the Amalgamated Association as an organization. This is final." And in November, the Amalgamated Association collapsed.

According to labor historian David Brody, in his highly acclaimed Steelworkers in America: The Nonunion Era, the daily wages of the highly skilled workers at Homestead shrunk by one-fifth between 1892 and 1907, while their work shifts increased from eight hours to 12 hours.

That was not the only measure of the steel workers' defeat. As Sidney Lens pointed out in his classic The Labor Wars: From the Molly Maguires to the Sit-Downs, membership in the Amalgamated Association plummeted from 24,000 to 10,000 in 1894 and down to 8,000 in 1895. Meanwhile, the Carnegie Steel Co.'s profits rose to a staggering $106 million in the nine years after Homestead. And for 26 long years—until the last months of World War I in 1918—union organizing among steelworkers was crushed.

At the end of the 19th century, Homestead inspired a song well known around the country, "Father Was Killed by the Pinkerton Men." The lyrics of this deeply angry ballad began: "'Twas in Pennsylvania town not very long ago,/Men struck against reduction of their pay./Their millionaire employer with philanthropic show/Had closed the works 'till starved they would obey./They fought for home and right to live where they had toiled so long,/But ere the sun had set, some were laid low."

Sources

Demarest, David (editor), The River Ran Red: Homestead 1892.University of PittsburghPress, 1992. Krause, Paul, The Battle for Homestead, 1880-1892: Politics, Culture, and Steel. University of PittsburghPress, 1992. McCollester, Charles, The Point of Pittsburgh.Battleof HomesteadFoundation, 2008. Brody, David, Steelworkers in America: The Nonunion Era. Harper & Row, 1969. Lens, Sidney, The Labor Wars: From the Molly Maguires to the Sit-Downs.Haymarket Books, 2008.