This 2020 edition of “Death on the Job: The Toll of Neglect” marks the 29th year the AFL-CIO has produced a report on the state of safety and health protections for America’s workers. This report features national and state information on workplace fatalities, injuries, illnesses, the number and frequency of workplace inspections, penalties, funding, staffing and public employee coverage under the Occupational Safety and Health Act. It also includes information on the state of mine safety and health, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

This December will be 50 years since Congress enacted the OSH Act, promising workers in this country the right to a safe job. More than 618,000 workers now can say their lives have been saved since the passage of the OSH Act. Since that time, workplace safety and health conditions have improved. But too many workers remain at serious risk of injury, illness or death as chemical plant explosions, major fires, construction collapses, infectious disease outbreaks, workplace assaults and other preventable workplace tragedies continue to occur. Many other workplace hazards kill and disable thousands of workers each year.

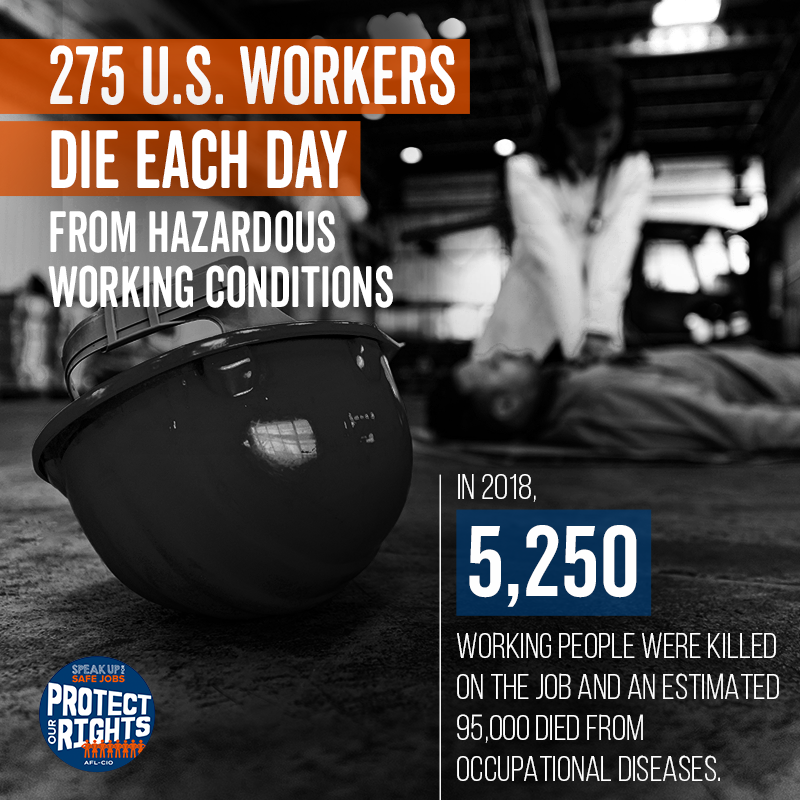

In 2018, 5,250 workers lost their lives on the job as a result of traumatic injuries, according to fatality data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS). The rate of fatal job injuries in 2018 remained the same as 2017, at 3.5 per 100,000 workers. Each day in this country, an average of 14 workers die because of job injuries—women and men who go to work, never to return home to their families and loved ones. This does not include workers who die from occupational diseases, estimated to be 95,000 each year. Chronic occupational diseases receive less attention, because most are not detected until years after workers have been exposed to toxic chemicals, and because occupational illnesses often are misdiagnosed and poorly tracked. All total, on average 275 workers die each day due to job injuries and illnesses.

Workplace deaths increased for Latino workers in 2018: 961 Latino workers died on the job, an increase from 903 deaths in 2017. The fatality rate among Latino workers (3.7 per 1000,000) continues to be higher than the overall fatality rate of 3.5 per 100,000 workers. In 2018, 67% of Latino workers who died on the job (641) were born outside of the United States. Fatalities among all foreign-born or immigrant workers continue to be a serious problem. In 2018, there were 1,028 workplace deaths reported for all immigrant workers, the highest number of fatalities in at least 12 years.

In 2018, workplace deaths increased for Black workers: 615 Black workers died on the job, an increase from 530 deaths in 2017 and a 46% increase in the last decade. The fatal injury rate for Black workers increased in 2018 to 3.6 per 100,000 workers from 3.2 in 2017, now higher than the overall fatality rate (3.5). This is the first time the fatality rate for black workers has been greater than the overall fatality rate in at least five years. The number of serious work injuries and illnesses also increased among Black workers (from 69,900 to 71,600). Workplace deaths increased among older workers (ages 55 and older). People are working longer, and the number of workers ages 55 years and older has increased 84% since 1999. BLS estimates this trend will continue, and that by 2029, one in four workers will be 55 years or older.

Workplace violence deaths increased (from 807 to 828 deaths) and are now the second-leading cause of job death. Since 2009, the workplace violence injury rate in private hospitals and home health services has more than doubled. During the Obama administration, the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) enhanced enforcement on workplace violence using the general duty clause of the OSH Act, updated guidance documents and committed to developing a workplace violence standard. But the Trump administration has failed to act; under his watch, OSHA has not met any of its deadlines to move the workplace violence rulemaking forward. In November 2019, the House passed the Workplace Violence Prevention for Health Care and Social Service Workers Act (H.R. 1309, S. 851), requiring federal OSHA to promulgate a standard to protect these workers at especially high risk of violence on the job, but efforts stalled in the Senate.

In 2018, nearly 3.5 million workers across all industries, including state and local government, had work-related injuries and illnesses that were reported by employers, with 2.8 million injuries and illnesses reported in private industry. Due to limitations in the current injury reporting system and widespread underreporting of workplace injuries, this number understates the problem. The true toll is estimated to be two to three times greater—or 7.0 million to 10.5 million injuries and illnesses a year. In 2018, state and local public sector employers reported an injury rate of 4.8 per 100 workers, significantly higher than the reported rate of 2.8 per 100 among private-sector workers.

The cost of these injuries and illnesses is enormous—estimated at $250 billion to $330 billion a year.

During its eight years in office, the Obama administration had a strong track record on worker safety and health, appointing dedicated pro-worker advocates to lead the job safety agencies who returned these programs to their core mission of protecting workers. The Obama administration increased the job safety budget, stepped up enforcement and strengthened workers’ rights. They issued landmark regulations to protect workers from deadly silica dust and coal dust, along with long-overdue rules on other serious safety and health hazards, including beryllium and confined space entry in the construction industry.

With the election of President Trump, the political landscape and direction of the job safety agencies shifted dramatically. President Trump ran on a pro-business, deregulatory agenda, promising to cut regulations by 70%. Since taking office in January 2017, the Trump administration has moved aggressively on its deregulatory agenda. Through executive orders, legislative action, and delays and rollbacks in regulations, the Trump administration has sought to repeal or weaken many Obama administration rules.

For the first two years of the administration, with Republicans in control of Congress, there was little oversight and only a limited ability to block these regulatory attacks and rollbacks. As a result, important safety and health protections have been repealed or weakened. There has been little action to address serious hazards like workplace violence, and no accountability or leadership of important agency work such as the infectious disease rulemaking that began in 2009. For the first two years of the Trump administration, job safety and health enforcement at both the Occupational Safety and Health Administration and the Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) largely had been maintained, but in the fall of 2019, OSHA began reducing inspections involving significant cases and complex hazards, and in the COVID-19 pandemic, has largely been completely absent from workplaces where they have the authority and responsibility to enforce workplace safety laws. At both agencies, the number of inspectors has declined significantly; OSHA has the lowest number of job safety inspectors since the early 1970s, when the agency opened, and MSHA is consolidating coal and metal/nonmetal inspectors into one.

President Trump has proposed cuts in in key worker safety and health programs in the budgets for FY 2018, FY 2019, FY 2020 and FY 2021, seeking to cut funding for coal mine enforcement; eliminate OSHA’s worker safety and health training program and the Chemical Safety Board; and slash the NIOSH job safety research budget by more than 40%. To date, Congress has rejected these proposed cuts.

President Trump nominated corporate officials to head the job safety agencies who had records of opposing enforcement and regulatory actions. David Zatezalo, a coal industry executive from Rhino Industry Partners, was nominated to head the Mine Safety and Health Administration and was confirmed by the Senate on Nov. 15, 2017. Scott Mugno, vice president of safety, sustainability and vehicle maintenance at FedEx Ground, first was nominated to head the Occupational Safety and Health Administration on Nov. 1, 2017, and then renominated on Jan. 16, 2019. Mugno withdrew his nomination in 2019 after the process stalled, and OSHA has not had an OSHA head for the entire Trump administration. Eugene Scalia, an industry lawyer with a decades long report card filled with opposition to and attacks on worker safety protections, was nominated as secretary of labor in July 2019 and confirmed in September 2019. Secretary Scalia led the industry opposition effort to OSHA’s ergonomics rulemaking, which was eventually successful but was repealed by Republicans using the Congressional Review Act—the first time it was ever used. He also opposed rules that require employers to pay for personal protective equipment (PPE) and many other rules, and is known for spreading misinformation and “blame the worker” messaging.

With the election of a Democratic majority in Congress in 2018, the political environment for safety and health improved. In the 116th Congress, Democrats moved aggressively on a proworker agenda, introducing progressive legislation and conducting rigorous oversight of the Trump administration’s policies and programs. In a divided Congress, pro-worker legislative progress stalled in the Senate, and even was blocked from consideration in committees. For the past six months, the Democratic majority has been focused on oversight of the Trump administration’s response to COVID-19 and aggressive COVID-19 safety protections and economic relief.

Nearly five decades after the passage of the OSH Act, the toll of workplace injury, disease and death remains too high. There is much more work to be done.

Digital Toolkit