The evidence has mounted, and is clearly accepted, that extreme income inequality has grown in the United States over the past 40 years—and by extreme income inequality, I mean a huge imbalance in income growth favoring the top 1% of the population. This is extreme because it is large enough and sufficiently imbalanced growth that it must force a rethinking of economic policies.

Too much of the debate has been taken up on wage disparities between high-tech workers and low-wage service workers, between those who program the robots and those displaced by them. All those debates are limited to understanding the stagnant income growth within those in the bottom 90% of the income distribution. In net terms, those workers have gained nothing.

Unfortunately, however, that framework continues to dominate the global consensus debating solutions to the rising inequality, whether it is from the International Monetary Fund or the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, pillars of the so-called troika of policy centers that define neoliberal consensus on best practices for national policy. And, the concerns about inequality echo through the World Bank and the World Economic Forum.

Recent research is pointing to a new direction of understanding why inequality hurts growth. It is based on micro-economic evidence of firm-level success and points to why policies aimed at reversing income inequality are in the interests of businesses at the firm level. By exploiting new big data, economists are modelling a different challenge that inequality creates.

Last year, Simon Gilchrist and Egon Zakrajšek looked at differences in pricing behavior of firms during the recovery from the 2008 recession and uncovered that firms live and die based on their customer base. Growth of the firm is reliant on growth of their customer base. Firms that face stagnant customer base growth and loss of customer base then live or die on the availability of credit and their liquidity. Those firms are fragile. A downturn like 2008 means they face the strongest headwinds, their customer base freezes or shrinks as their incomes fall and their lack of credit from the financial collapse can easily mean they fail, or struggle to hold on by raising prices to their remaining customers.

The macro-economic implications are clear. If the bottom 90% of the income distribution rises by only 0.7%, then there will be a lot of firms facing no growth in their customer base. Another new study this week confirms that. Xavier Jaravel shows that those with low incomes consistently buy the same products year to year. This follows basic economic rationality. Consumers with the same income, assuming fixed tastes and preferences, should be observed buying the same things over time. Having revealed their preferences for goods, if their incomes don’t change, their preferences should also be stable over time. In business terms, they do not present themselves as new customers. So, firms do not chase them. These same consumers, therefore, do not realize any gains from “competitive” markets, fighting through prices to win dominance over new products. Instead, the firms that serve the poor are the firms Gilchrest and Zakrejšek point out must survive on raising prices to hold onto their total revenue during tough times.

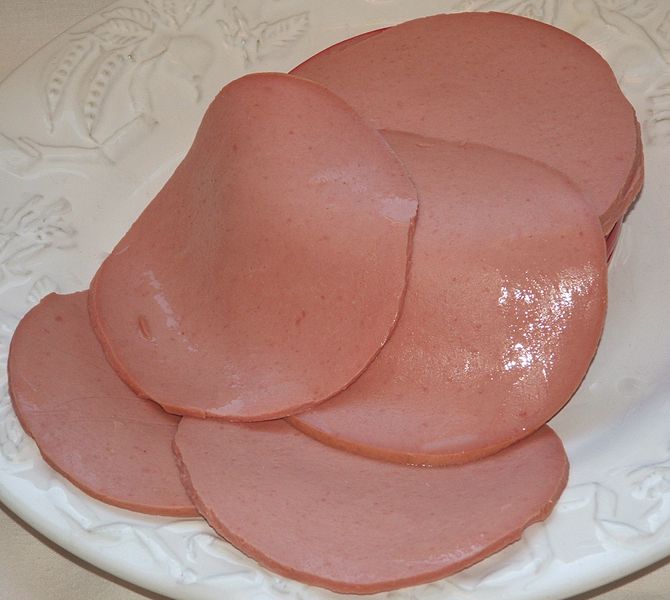

The rich, Jaravel found, on the other hand, face great competition for them among firms chasing expanding customer bases. In short, the rich are not poor people with more money. They do have different tastes; as economic theory suggests, rising incomes change people’s tastes and preferences. Economists, in fact, label some goods as inferior goods because as incomes rise, demand for them falls; the rich buy foie gras, not baloney, craft beers, not Bud Light. When firms chase those customers, they compete, and the benefit is falling prices for those goods.

So, there are two distortions that hurt growth when income grows so unequally. First, if income grows equally, then the 127 million American consumer units (households and families that buy things) all become potential new customers. Firms would then chase them, and the competitive dynamics of the market would create new opportunities to grow or create businesses. But, when only 1% have rising incomes, that is a growth of 1.2 million potential new customers. That is a vastly smaller set of opportunities for firms to grow.

Second, it is a limited set of tastes and preferences to go after; it is a market that lacks the scale for creating large numbers of jobs and production efficiencies that come from a mass market of 127 million new customers. This hurts productivity growth, as more jobs are created and aimed at smaller scale production.

So, rather than ask individual firms, "What would a $15-an-hour wage mean in paying their workers?" firms should be asked, "What would a 100-fold increase in their customer base mean?" Most firms are more concerned about the latter, without an understanding of ways to make that happen. But, if the economy is to grow, be dynamic and benefit workers and companies both, companies need to think about what policies make growth more equal.