The effort to expand cynically named "right to work" laws says a lot about what is wrong with politics in our country. Disguised as protecting workers, the real goal is to silence workers’ voice, reduce our bargaining power and make our jobs more precarious. It’s about power—social, political and economic power.

After years of deceptive messaging, most people have the misconception that state law can force a worker to join a union. The reality is that no federal law and no law in any state can force a worker to join a union.

That’s good. No state or federal legislator should tell you when to join a union or when you can’t. This is a decision for you, your co-workers and your employer.

There is one and only one way to have the situation where all workers contribute to their union. If your workplace has agency fee or fair share fees, it’s because your co-workers demanded it and fought to write it into your contract. AND the employer agreed. AND your co-workers ratified the contract. In each subsequent round of contract negotiations, both sides ratify it again.

This condition becomes part of the collective bargaining agreement—"the contract"—which is just that, a legally binding contract between two willing parties.

To conservative thinkers, a contract is an object of reverence. Government shouldn’t interfere with a contract between two willing parties. The cynically named right to work legislation really forbids workers and employers from writing mutually agreed contract language that recognizes working people’s voice at work.

Let’s be clear. We could certainly use more rights at work. The Bill of Rights in the Constitution does not apply inside the workplace.

Most employers have near-total authority over employees regarding hiring, firing, transferring, moving work locations and assignment of work to employees. An employer can insist that all workers listen to anti-union speeches. In the workplace, an employer can search your belongings, tap your phone, read your email, tell you when and where you can eat, prohibit you from smoking, and tell you what you can and can’t read on the internet.

State and federal laws protect military veterans, women, older workers and certain protected classes. Beyond that, in most states you can be fired for almost any reason, or no reason at all.

Champions of right to work argue from a cynical pretense that they care about workers. They don’t.

If disingenuous right to work groups wanted to protect working people, they would champion free speech and due process in the workplace. They might insist that you could only be fired for just cause; and that workers not be disciplined for something they wrote on Facebook on their private time. Right to work advocates might restrict "non-compete" agreements that block working people from seeking new jobs, or they could strengthen control of patent rights for employees.

The cynicism of right to work is in its true purpose—to weaken unions, and minimize one of the few remaining institutions of civil society that speaks for working people and communities.

The cynical premise of right to work laws is that working people have too much power. They can overwhelm helpless employers. Particularly, they say, local, state and federal governments are unable to resist the power of public employee unions.

It’s worth stopping for a second to look at wages levels for public employees—teachers, legislative staff, fish and game agents, national park rangers, nurses at Veterans Affairs hospitals, and Cabinet members in the White House. No one goes into public service to get rich.

Public employees are driven by mission. They almost always could make more in the private sector.

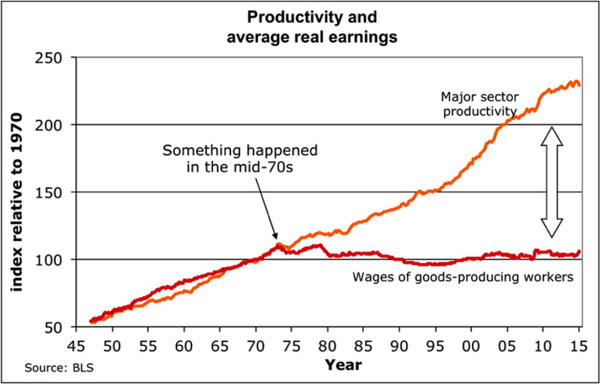

While productivity has gone up steadily, wages in America have been stagnant for decades. Who got those gains from productivity?

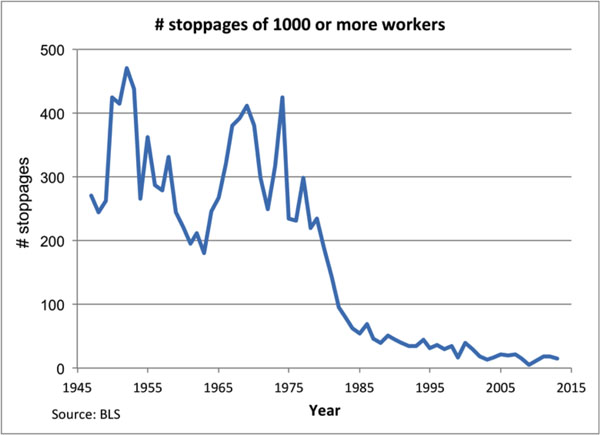

For 30 years, we’ve heard promises that gains will trickle down to us. A more realistic strategy for higher living standards is for us to demand a share of the gains we create. In the post-war period, working people were able to demand a share of the gains they created. They could bargain, with the potential to strike. If one union strikes, another group of employees have that example of strength to bargain with their employer.

Since the mid-1970s, strikes have become more rare. Employers have moved work to low-wage locations with weak labor laws. Bargaining power for working people is at historic lows.

It is tough to argue that workers have too much power. It is even tougher to tell workers that everything will be fine if we just lower our standard of living faster by weakening unions.

Canadians understand the deceit underpinning right to work. Canada made labor rights a key demand in renegotiating the North American Free Trade Agreement, a trade deal between Mexico, the United States and Canada. Canada wants the U.S. to end right to work.

A Canadian labor leader put it this way: "The United States has two problems. Number one is Mexico, number two is themselves. Canada has two problems: Mexican [wages] and right to work states in the United States."

Right to work falsely claims to be about free speech. Courts already have carved out religious objectors and provided an opt-out regarding union expenses for legislative lobbying.

If you believe in collective bargaining and the legitimate role of unions in civil society, then the right place to deal with union dues is in collective bargaining between workers and employers. That’s exactly what collective bargaining is for.

This post originally appeared at The Stand.