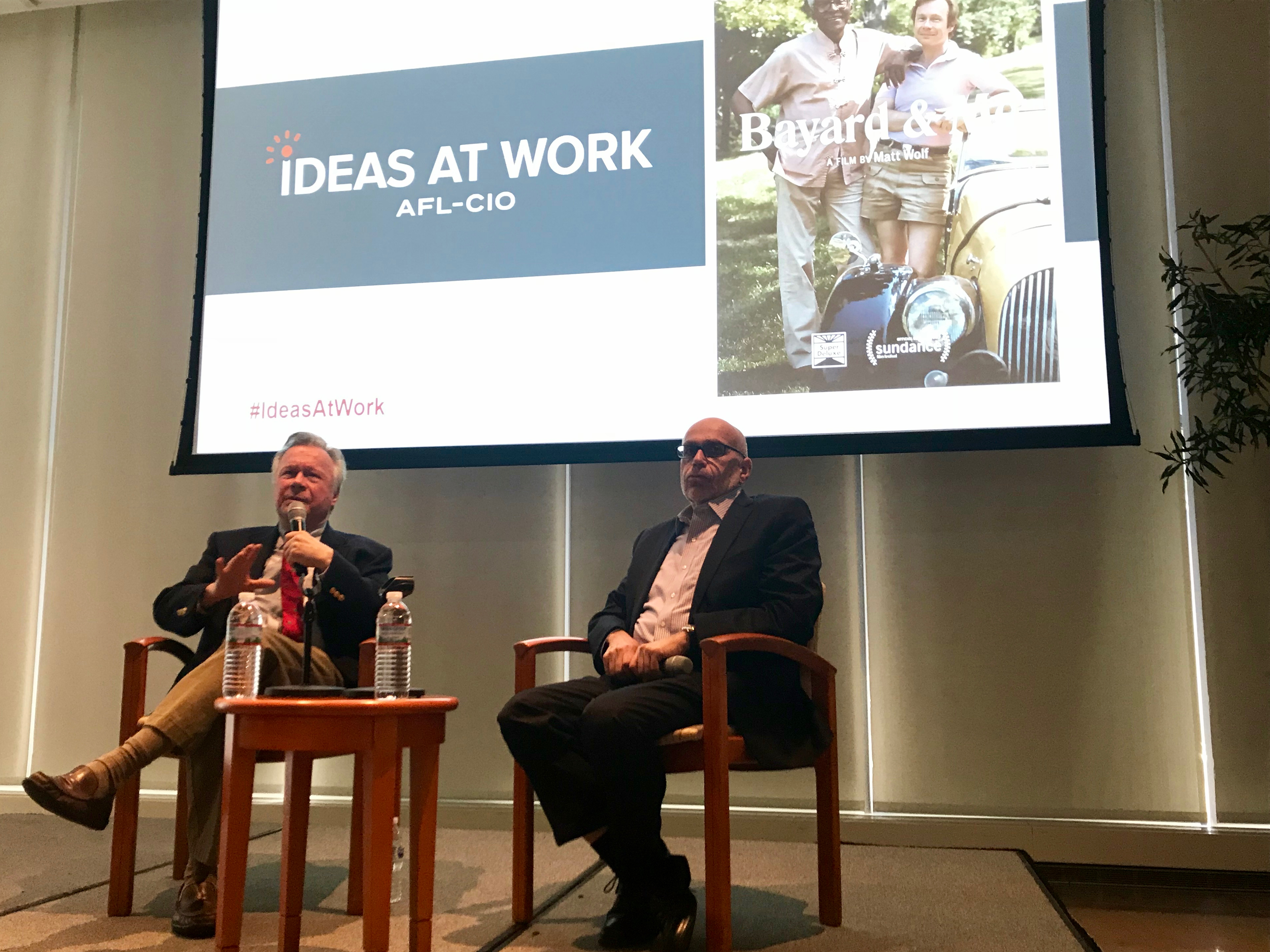

June is Pride Month. We are proud of the LGBTQ labor leaders who blazed a trail for dignity and equality. None had a greater impact than Bayard Rustin. To celebrate Rustin's life and legacy, the AFL-CIO, through its Ideas at Work series, hosted his longtime partner, Walter Naegle, for a screening of the award-winning documentary "Bayard & Me." The event was co-sponsored by Pride At Work and the A. Philip Randolph Institute. Following the screening, Naegle participated in a wide-ranging discussion with Stuart Appelbaum, the openly gay president of the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union. Naegle provided a firsthand account of Rustin's triumphs and tribulations as he faced incredible political and personal challenges during the civil rights movement. And both Naegle and Appelbaum talked about where we go from here.

The following are Naegle's remarks, as prepared:

I want to thank Tim Schlittner and Christine Cafasso for inviting me to join you for this showing of "Bayard & Me," and to Pride At Work and APRI for co-sponsoring it. Matt Wolf's film, which premiered at the Sundance Film Festival in 2017, has received much exposure over the last year and was nominated for a "Webby" Award—prizes for films made for the internet.

I'm going to make some brief remarks and then we will move into a discussion/Q&A session. I much prefer those to just giving a speech, and I believe that Bayard was of a similar mind. There was nothing he enjoyed more than a lively exchange based on facts, logic, reason, in an effort to get to the truth. You remember those, don't you?

I'm going to start with a few facts that may seem unnecessary, but in these times it is sometimes important to keep things simple and, for lack of a better word, "straightforward." Maybe we could call these "ground rules"—the facts and the choices that shaped his life and enabled him to make his mark.

Bayard Rustin was a human being, a man, a black man, a gay man, and a Quaker. The fact that he was black and gay made him a target for discrimination and persecution throughout his life. That he chose to be a Quaker meant that he equipped himself with the tools to address discrimination and bigotry with humanity, understanding, and love, never resorting to the tactics of hatred and oppression used by some of his opponents.

His evolution as an activist moved him from his start as a radical Christian pacifist to being a more pragmatic political person willing to negotiate and compromise for the greater good of a movement rather than hold to an absolutist position in the name of political purity. He moved, in the words of his most famous article, "From Protest to Politics," and grew to recognize that democracy is perhaps the closest thing we have to a political expression of the philosophy of nonviolence. He came to understand that through democracy we can come close to achieving those values that were instilled in him by his grandmother, Julia Davis Rustin, and which informed his lifelong activism—the belief in the oneness of the human family, the presence of the divine spirit in every person, integrity, and working for equality and justice.

One example of his commitment to working for a more just society was his long association with the labor movement, especially his close ties to his mentor A. Philip Randolph, founder of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, and Don Slaiman, head of the AFL-CIO's Civil Rights Department during the peak years of the African American struggle. Randolph saw organized labor as the vehicle for African Americans to achieve economic uplift and move toward social equality. He and Bayard instinctively understood that when legal barriers to equality were lifted—Jim Crow laws, school segregation, voter suppression, and others—that the issue of economics would take a front seat. Centuries of second-class citizenship, schools that were separate but not equal, poor housing, lack of proper health care, would result in a disproportionate number of impoverished blacks and the solution would require a national commitment to the eradication of poverty. But they also knew that a program targeting only African Americans was not politically viable. In 1965, under the auspices of the A. Philip Randolph Institute, they proposed A Freedom Budget for All Americans, a plan to eliminate poverty within a 10-year period. Although there were congressional hearings about the Freedom Budget, the plan never took off, largely because of the disproportionate funds that were being spent fighting the Vietnam War. The budget could be credited with influencing President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society initiative. Now 50 years later, eradication of poverty is again under discussion, with some proposing a guaranteed annual income for all, a proposal that was included in the Freedom Budget.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. increasingly supported the call for economic justice and the connection between the labor movement and the black working class. He was assassinated in Memphis while mobilizing support for the striking sanitation workers there who sought better wages and working conditions. His Poor People’s Campaign that was carried on by his successors sought to address the issue of poverty. Today, we have a new Poor People's Campaign—a National Call for Moral Revival, supported by a coalition of labor unions, faith-based organizations, civil and human rights groups, and other progressive entities, including APRI and the National LGBTQ Task Force.

In the years since his death, Bayard’s life and work have been recognized through a variety of initiatives, many spearheaded by the LGBT community. During his centennial year, APRI organized a special tribute to Bayard, its founding executive director. 2013 brought the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, and much of the coverage featured Bayard, something that was not done in 1963. A posthumous Presidential Medal of Freedom was awarded in November of that year by President Barack Obama. A number of community centers and political clubs carry Bayard’s name, as well as a high school in his hometown [of West Chester, Pennsylvania]. A few weeks ago, the school board in Montgomery County [Maryland] voted to name an elementary school after Bayard. Later this month, a plaque will be installed outside of Bayard's residence in New York City, which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 2016. His home for 25 years, and Randolph's for ten, Penn South was founded by the International Ladies' Garment Workers Union to provide decent, safe, and affordable housing for its workers and members of the community.

If you would like to learn more about Bayard, there are a number of biographies available, including Jervis Anderson's Bayard Rustin, Troubles I've Seen, John D'Emilio's Lost Prophet: The Life and Times of Bayard Rustin, and one for young readers Bayard Rustin, The Invisible Activist. "Brother Outsider: The Life of Bayard Rustin" is an award-winning full-length documentary. You also can visit the website: rustin.org.