History has long been portrayed as a series of "great men" taking great action to shape the world we live in. In recent decades, however, social historians have focused more on looking at history "from the bottom up," studying the vital role that working people played in our heritage. Working people built, and continue to build, the United States. In our new series, Pathway to Progress, we'll take a look at various people, places and events where working people played a key role in the progress our country has made, including those who are making history right now. Today's topic is the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.

We recently marked the 56th anniversary of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The full title makes it clear that the historical touchstone was about civil rights and worker rights. And the labor movement was key to the success of the march.

By any account, the march on Aug. 28, 1963, was a success. More than 250,000 people participated in what was then the largest demonstration for human rights in U.S. history. The pathway that led to the march started much earlier.

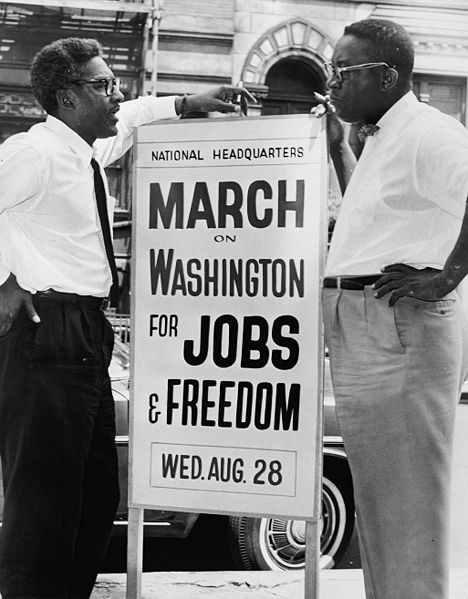

A. Philip Randolph, a leader in both the civil rights movement and a labor organizer with the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, began pushing for a march on Washington as early as 1941. Randolph, labor activist Bayard Rustin and others nearly pulled off a march that year, but it was called off late in the organizing. From then until late 1962, Randolph got little response from civil rights leaders. Changing this would be a key to pulling the march off. He worked with the heads of the "Big Six" civil rights organizations, which included not only Randolph's Sleeping Car Porters, but also the NAACP, the National Urban League, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Conference of Racial Equality and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee.

That began to change once Randolph and Rustin got together to plan a march commemorating the centennial of the signing of the Emancipation Proclamation. In early 1963, Bull Connor became national news when he turned fire hoses and attack dogs on children and then attitudes about the march quickly changed. Rustin was to originally direct operations for the march, but when some activists balked at having a homosexual man as the face of the march, he was replaced by Randolph.

Rustin continued to organize the event, however, and leading up to the march, they faced tough challenges, including bringing together civil rights leaders, defending against attacks from segregationists, moderates who wanted a slower approach to progress and the logistics of the largest peaceful protest in the country's history.

The influence of Randolph and Rustin on the agenda of the march was obvious. Among the list of demands the marchers presented were: a massive federal jobs and training program for unemployed workers, a national minimum wage that provided for a decent standard of living, an expansion of the Fair Labor Standards Act to include all areas of labor and a federal Fair Employment Practices Act barring discrimination in government hiring at all levels.

Labor's influence on the march wasn't limited to leadership. The UAW provided much of the funding for the march. Randolph's Sleeping Car Porters helped transport thousands of demonstrators to and from the event. And many unions participated in the march, either officially or unofficially, as their members joined the cause.

One of the most important and memorable events in American history was not only a civil rights event, but from beginning to end, a demonstration on behalf of working people. We face many of the same issues in our current political climate, and the efforts that led to the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom provide us with inspiration to continue building an America where all working people can thrive.