History has long been portrayed as a series of "great men" taking great action to shape the world we live in. In recent decades, however, social historians have focused more on looking at history "from the bottom up," studying the vital role that working people played in our heritage. Working people built, and continue to build, the United States. In our new series, Pathway to Progress, we'll take a look at various people, places and events where working people played a key role in the progress our country has made, including those who are making history right now. Today's topic is the story of Baltimore caulkers who bought their own shipyard in the face of systemic discrimination.

Pro-slavery forces before the Civil War often used racist appeals to labor in their efforts to sway public opinion. They fear-mongered that freed Black workers would undercut White workers in the labor force and would cost jobs and drive down wages. Free Black workers, before and after the war, were often used as scabs, and they couldn't refuse the offer, as other work options were limited or non-existent.

As a response, Black workers began forming their own labor associations. Among the first formed was by caulkers in Baltimore in the early days of the Reconstruction Era. Before the war, White caulkers used violence and intimidation to scare Black caulkers out of the trade. The violence continued after the war, and in October the White caulkers, supported by ship carpenters, went on strike to get Black workers fired as caulkers and longshoremen. The strike was successful with the support of city government and local police. More than 100 men found themselves out of work.

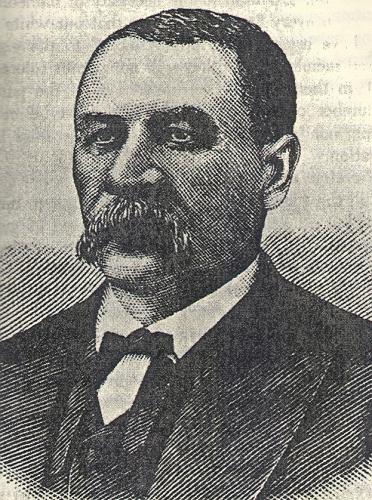

One of those men, Isaac Myers (pictured) proposed that they form a union and raise funds to purchase their own cooperative shipyard and railway. The campaign began and they issued stock that quickly raised $10,000 from the Black population of Baltimore and beyond. One of the first stockholders was Frederick Douglass. They secured a $30,000 loan from a ship captain and were able to buy an extensive shipyard and railway and founded the Chesapeake Marine Railway and Dry Dock Company in 1866.

They soon employed 300 Black workers and paid them an average wage of $3 a day. They were able to win several government contracts, and they paid off the debt from the loan early. The shipyard expanded and soon they were hiring White workers, too. The Colored Caulkers' Trade Union Society of Baltimore was a success under the leadership of Isaac Myers, who was elected president. He established relations with the White caulkers union and the two groups began to work together to address common problems.

The model used by the caulkers worked well in the North, but raising similar funds in the South was much more difficult. But they still took inspiration from the Baltimore success and began to organize and strike, leading to some of the largest mass demonstrations in the history of the South. Some had success and a growth of Black entrepreneurship was an outgrowth of the Baltimore caulkers' efforts as was the fact that the Black working class had now joined the labor movement.

Source: "Organized Labor and the Black Worker, 1619-1981" by Philip S. Foner, 1974.