This post originally appeared at Medium.

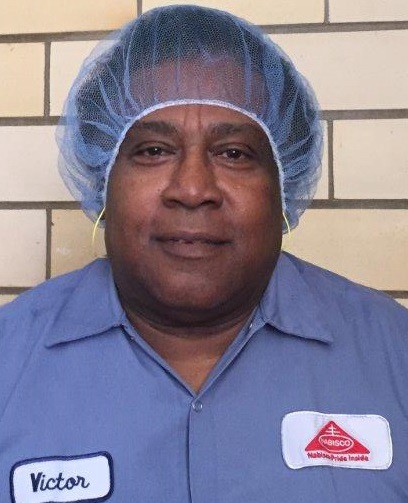

As told to me by Victor Weekes.

At 4 a.m., the bridge from Washington to Oregon is gray and quiet. The seasons pass quickly after 41 years, but every morning the drive is just a little different. You’ve got to pay attention to the details. Otherwise, life just passes you by.

I get to the facility at 5:15 a.m., hit the clock at 6 and punch out at 2. Like many of us, I pride myself on my professionalism and work ethic. We make Oreo cookies, Ritz Crackers, Chicken in a Biskit, Chips Ahoy! and Wheat Thins. Good stuff.

We set a high bar, but managers aren’t keeping up. You wouldn’t believe the kinds of insults and bullying we deal with daily. It’s not a reflection on us, but it says everything about Mondelez International. You probably know that Mondelez owns Nabisco and many of our popular American snack brands.

So here’s the deal: We’re a good group of people. We work hard and produce value for Nabisco over the long term. We have a union, too, so some of that value comes back to us. I’ve got a home, and my four kids have been able to get good educations and good jobs. We bargained hard for retirement security and gave up a lot to get it. I sure hope it’s there for me. I’m counting on it. Too many of our new managers are ignorant of Nabisco’s history, what this company has been to so many of us and what it can still be.

I’ll tell you about it. I’m a 71-year-old black man from Barbados. I’m proud of my heritage, and I’m proud to work at this plant. We have folks from all around the world. We used to say we’re like the United Nations. We all get along.

America needs places like this, where folks can get ahead by working hard and playing by the rules.

But the cooperative union culture we built here with Nabisco is in danger. The young people are scared.

Every day we go to work and wonder if today is the day they’ll announce our jobs are going to Mexico. They’ve been chipping away at us in every Mondelez plant across the country. There’s always that threat over your head, and it’s real.

Right now, hundreds of jobs are set to leave Chicago. Other plants have closed as jobs have been shipped to Mexico. And our union contract has expired here in Portland, Ore.

When I was a kid in Barbados, my dad joined the U.S. Coast Guard. I followed in his footsteps by becoming a merchant seaman for a British company, and after being laid off, I started working ships up and down the West Coast. That’s how I fell in love with Oregon and Washington, and with my wife.

Work comes and work goes. You know how it is. I ended up working for Boise Cascade, a lumber company, until I got laid off in 1975.

I came over to Nabisco because I heard I wouldn’t be discriminated against. And I wasn’t.

I was treated fairly. I started off in the mixing department. Back then, it was hard, physical work. We’d cut open the 150-pound bags of flour and cocoa and mix in the oil and water. Since then, I’ve held about every job in the plant. These days I’m the floor supplier , which means I supply all the raw materials to all six lines in the packing department.

We’ve had a parade of corporate owners over the years, but Mondelez is the worst. They don’t give a damn about customers, and they don’t give a damn about the people who make the products.

They tell us—I’m not kidding—to get the hell out.

They literally harass me to quit, because they don’t think I’m worth my wage. They tell that to all the old-timers. It’s disrespectful. But I’m staying, because I won’t let them push us around. Our jobs are important, not just for ourselves and our families, but for America. Unionism makes us strong and makes America a better place. And we’re going to show the American public how to use unity to turn bad jobs into good jobs, and how to beat back every executive who wants to turn every job into a bad job.