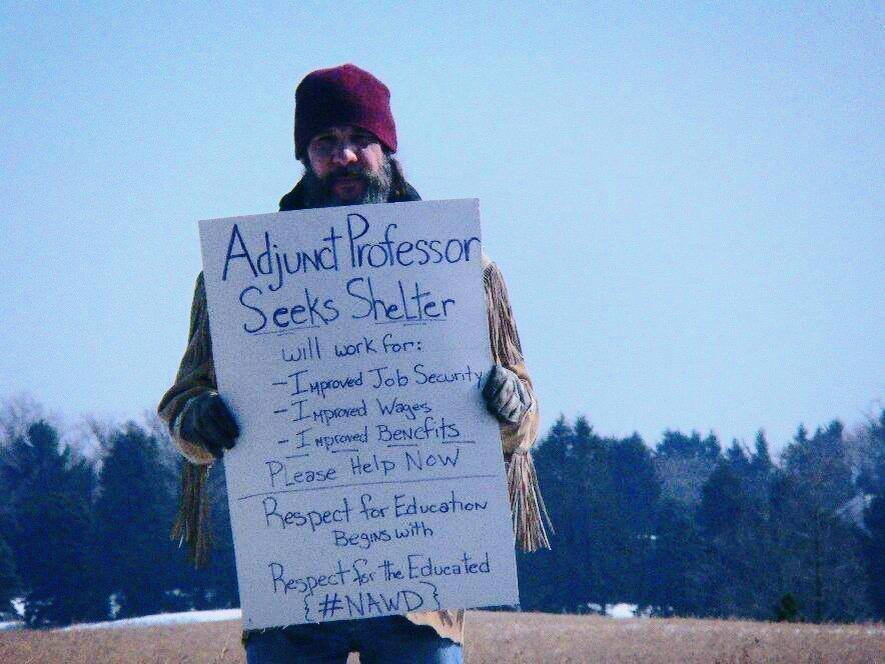

If you spend much time talking to adjunct professors across the United States, you start to realize that it sounds a lot like what fast food workers fighting for better wages and working conditions are saying. When you take a deeper look at how U.S. colleges and universities treat adjuncts, you understand that it's an apt comparison.

Gawker asked actual adjuncts to tell the stories of their workplace environment. These stories are filled with details that sound like they come from minimum wage fast-food employees. And this is from an industry where the working people involved are required to have an advanced education (and likely the associated student loan debt) and are in charge of educating the future workforce and leaders of the country.

This is a problem. And it's a big one.

Personally, I taught as an adjunct professor for about a decade. I taught at various community colleges in Florida. And I can vouch for all of these complaints and many others. Here are some of the key negatives I experienced working in a job that I loved. Teaching is a great job. You get to help shape the future of the country (and as a college professor, you get a lot of international students, too) and helping move young people from unsure about their future to a career path is one of the more rewarding things you can do. So the problems come not inherently from the job, but from the people who run these schools and are, increasingly, not from educational backgrounds, but from business ones. That's no way to run an educational institution.

Here are seven common ways that colleges and universities mistreat adjunct professors:

1. Horrible pay: According to a recent study, the average adjunct gets $2,700 per course. When I worked as an adjunct in Florida, only one college ever paid more than $2,000 to me for any class I taught. That's for a weekly schedule of three hours of in-class instruction, one office hour and however much preparation and grading time you need outside of class. Over a four-month semester, it'd amount to about 30 hours in-class, 30 hours in the office and more than three hours a week of grading and preparation, adding up to 150 hours of work, work that requires an advanced degree. In my best-played class as an adjunct, that works out to about $14 an hour. That's gone up a bit since I last taught in 2012, and it varies by state, but for a job that requires a college degree, it pays less than what fast-food workers are fighting for as a minimum living wage right now.

2. Not enough hours: Every school I worked at either limited the number of hours an adjunct could teach to at least one class less than full-time professors got or had so few available classes for adjuncts that few adjuncts ever teach more than two classes at the same college at the same time. In the more than 10 years I taught as an adjunct, I taught more than three classes at the same school only twice. That means that if I did what most people do and went to one workplace and worked the maximum hours I was allowed, I would have still made less than $20,000 a year. For a job that required me to have a master's degree.

3. Strong financial limitations: When you make less than $20,000 a year, you aren't making enough to survive. You have to find additional income. Having a spouse with a good income helps, but one shouldn't have to marry to survive. And if you have children, you better have a spouse who makes a ton of money because the school isn't going to help you meet your financial needs. Many adjuncts have no option but to take another job. For me, I had to scramble for years to make ends meet. I stayed in graduate school and took out loans to help pay the bills, even after I got my master's. I taught at multiple schools, but I found that most universities don't hire adjuncts except in shortages or emergencies. They tend to use graduate assistants (who they don't have to pay a salary in many cases). And since community colleges tend to be spaced out to serve diverse geographic populations, the closest schools to where I lived (beyond my first college) were all more than an hour away. At a time when gas prices were high, that meant that driving to a second school (or third, one semester) meant that the gas money it took to get to work nearly took out all of the income I made for driving that far in the first place. I couldn't find many flexible jobs that would allow me to take off one to three hours a week to go teach classes, so I had to find flexible work or do freelance gigs.

4. No job stability: Getting to teach a class one semester is no guarantee that an adjunct will get a class the next semester. Even if you're good at it. I always got great student evaluations and volunteered to help sponsor student organizations, even chaperoning students on out-of-town field trips. And while many semesters I got the maximum number of classes possible (three at my main school), there were individual semesters where I only got offered one or two classes. My bills didn't go down those semesters, I just had less income. And had to scramble to find work every four months. And let's not even talk about the lower course loads that are available in summer, where the idea of an adjunct at most schools getting a full course load is far-fetched, especially if the full-time professors wanted to teach in the summer to get extra money. If the full-time professors needed the summer classes, imagine what this means for adjuncts. And, since you have no contract and no one to bargain on your behalf, you can just be out of a job any semester. With no cause necessary and no recourse.

5. Very little room for advancement: Full-time professor jobs, even at community colleges, rarely go to teachers without a Ph.D. And that is the only career advancement, within the field, for adjuncts. Full-time professor jobs are great jobs. And people don't leave them often. And schools don't add new ones often. So those jobs become highly competitive and, in weak economic times, the qualifications of the applicant pool increase. Finding a full-time job as a college professor is difficult. In the many, many times that I applied for full-time jobs over a decade, I only got an offer once. I took it. It paid $29,000 when I started and I had to live in the middle of nowhere in Florida. You've heard of manatees? They only really live in one place in the wild. That's where I taught. I did a good enough job for the two years that I was there, that I was running for faculty senate president unopposed, the school offered me tenure a year early, and the students voted me into the college's Faculty Hall of Fame, after I did things like help the student government win awards and taught the first classes in the county about black history and women's history. And I had to leave the job because of the terrible pay. Now, think about what the adjuncts at that same college were making. I got about a dozen or so other interviews during that decade, but that was the only time I got a full-time offer.

6. Few, if any benefits: Most of the time, adjuncts at most colleges and universities get limited or no benefits. No insurance, no sick leave (find a replacement for your class if you are sick or get your pay docked), no vacation, no nothing. Crappy wages and that was it. Once a semester, we had an adjunct appreciation day and we got a few free slices of pizza. If we taught that day, or could make a special trip out to campus, wasting the gas money they weren't paying us.

7. Little institutional respect: The colleges I worked at were pretty bad in their treatment of adjuncts. Not the departmental deans and program chairs, those people, at least in my experience, were mostly former teachers and were very respectful and sympathetic. And their hands were tied by higher level administrators who didn't really care much at all about adjuncts. Few schools take steps to address the problems listed above. And many are openly hostile. At one college, I was told that no one was allowed to talk about unions, even in faculty senate meetings. Any such thing had to be done off campus. At another school, the faculty union president told me that, as an adjunct, I should stop coming to union meetings. He said that he couldn't protect me from retaliation. When I saw the school president at a Republican Party election night party, as a big donor to the candidate, I knew that I should stop going to union meetings if I wanted to be able to pay my rent. At none of the schools, all of which were in the heat and humidity of Florida, did I get a parking spot. In all of them, I had to fight with students to find a spot in a student lot. One school had a faculty lot that we could park in, but it sometimes filled up and it was literally at the opposite end of the campus from where I taught (a campus with more than 10,000 students, so we aren't exactly talking a short walk). Most of the time, I didn't even have access to an office where I could talk privately with students about their grades or provide them with assistance in an environment where they could talk freely. I've even seen colleges play adjuncts and full-timers against each other. After the faculty senate at one school (out of solidarity) requested higher pay for adjuncts, the college president told the full-timers that the adjuncts could get a boost in pay, but it would have to come out of the full-timers' salaries. Not surprisingly, none of the full-timers was inclined to cut their own pay in order to raise that of adjuncts. And they shouldn't have to.

One last thing to keep in mind: Adjuncts literally do the same job as full-time professors. In-class instruction, class prep, grading, student conferences, administrative requirements—all these things are identical for adjuncts and full-time professors. Full-timers might have to teach one or two more classes (for a starting salary at most places that is three to four times higher, and much higher as a full-timer stays at the school longer), and they might have to sit on one or more college committees and attend a few extra meetings and such, but usually these types of meetings and things come out of the standard work hours of that full-timer and require no extra commitment of time. The work that full-timers do is an important part of making a college or university function, so the solution isn't to go after them and call for cuts or extra work. The solution is to treat adjuncts as if they are doing the same work as full-timers because they are already doing so.