As we celebrate Black History Month, we thought we'd take a look back at some of the women who have made history in the realm of fighting for the rights of working people. The battles they fought at the intersection of the rights of African Americans, women and working people should have made these women household names. Women continue to be at the forefront of battles for the rights of African Americans today, building on the work of these women and many others. Here is an introduction to a group of amazing women who did some amazing things.

Hattie Canty

Hattie Canty grew up near Mobile, Alabama, before eventually settling in Las Vegas with her family. In 1972, she began working various jobs as a maid and janitor. She became active in the Culinary Workers Union Local 226 and was elected to the local's executive board in 1984, the year they staged a 75-day walkout to improve health insurance for casino workers. In 1990, she became the president of the union, and in 1991, the Culinary Workers began the longest labor strike in American history, with a walk off from the Frontier Hotel over unfair labor practices. Six years later, the hotel's new owner settled with the union. Canty not only fought to make sure that working people got paid the living wages they earned, she helped integrate the union, helped people of color obtain better jobs and established the Culinary Training Academy, which teaches job skills necessary for employment in the hospitality industry.

Key Quote: "Coming from Alabama, this seemed like the civil rights struggle….The labor movement and the civil rights movement, you cannot separate the two of them."

Watch this video (below) to learn more from Canty.

Velma Hopkins

In the 1940s, Velma Hopkins, a member of Local 22 of the Food, Tobacco, Agricultural and Allied Workers of America-CIO, led a fight for better conditions for African American workers in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. The union challenged R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Co. to improve conditions for black workers, who endured segregated work areas permeated by oppressive heat and dangerous tobacco dust. A series of strikes and campaigns led to job security, wage increases and other benefits. The work Hopkins did in leading the fight inspired many North Carolinians and helped establish what would become Winston-Salem's black middle class.

Key Quote: "I know my limitations, and I surround myself with people who I can designate to be sure it’s carried out. If you can’t do that, you’re not an organizer."

Lucy Gonzales Parsons

Lucy Gonzales was born a slave in Texas. After emancipation, she married Albert Parsons, and white supremacists drove the activist couple from their home state. Settling in Chicago, Lucy and her husband began organizing on behalf of the city's industrial unions. In 1886, the couple helped lead 80,000 working people in the world's first May Day parade, which demanded the eight-hour day. After her husband was arrested, along with seven immigrant leaders, during the Haymarket Riot, Parsons became active in the campaign to free the men. She soon became known by anti-union forces as "more dangerous than a thousand rioters." Her activism in the following years would lead her to become the only woman to speak at the founding convention of the Industrial Workers of the World. She actively fought for working people until she died in a fire in 1942.

Key Quote: "Governments never lead; they follow progress. When the prison, stake or scaffold can no longer silence the voice of the protesting minority, progress moves on a step, but not until then."

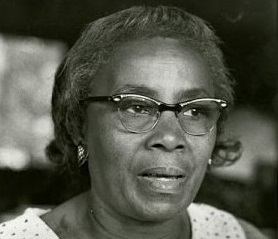

Rosina Tucker

The daughter of former slaves, Rosina Tucker was born in Washington, D.C., in 1881. A talented musician, she pursued a career as a file clerk with the federal government. She married Berthea J. Tucker, a Pullman car porter, in 1918. When the porters began to organize the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters under the leadership of A. Philip Randolph, Tucker joined in the membership drive and not only helped recruit many of the union's members, but also helped found the organization's women's auxilliary. As the union grew, the auxilliary did as well, eventually gathering more than 1,500 dues-paying members. She passed in 1987, after years of activism for civil rights and labor causes. The span of her years of dedication was so broad that she was both a mourner at the 1895 funeral of Frederick Douglass, and an organizer at the 1963 March on Washington.

Key Quote: "Once a young man asked me, 'What was it like in your day?' 'My day?' I said, 'This is my day!'"

Sue Cowan Williams

In 1910, Sue Cowan was born in a small town in Arkansas. After college, she became a teacher in Little Rock and married her first husband. In 1942, she became the plaintiff in a class-action lawsuit that sought to eliminate the pay disparity between black and white teachers. After a weeklong trial, she lost the trial. In 1945, though, an appeals court decided to overturn the ruling, but not before the school district had fired her, along with the principal of her school and the president of the City Teachers Association of Little Rock. In 1952, Williams would get her teaching job back and remained active in her community until she passed in 1994.

Septima Poinsette Clark

Septima Poinsette Clark was born in 1898 to a laundrywoman and a former slave in Charleston, South Carolina. By the time she was 20, she began a teaching career that lasted more than 40 years. While teaching, she pursued higher education and activism. She participated in a class-action lawsuit that led to pay equity for black and white teachers. In 1956, she was fired after the state passed a statute prohibiting city and state workers from belonging to civil rights organizations, when she refused to resign from the NAACP. From that point forward, she was an active participant in the civil rights movement, including teaching many workshops and classes that empowered and inspired activists, including Rosa Parks, who took one of her workshops just months before the beginning of the Montgomery bus boycott. In 1975, she was elected to the Charleston School Board; and the next year, the governor of South Carolina reinstated the teacher's pension that had been unjustly taken from her 20 years earlier.

Key Quote: "My philosophy is such that I am not going to vote against the oppressed. I have been oppressed, and so I am always going to have a vote for the oppressed, regardless of whether that oppressed is black or white or yellow or the people of the Middle East, or what."