Throughout Pride Month, the AFL-CIO will be taking a look at some of the pioneers whose work sits at the intersection of the labor movement and the movement for LGBTQ equality. Our next profile is Miriam Frank.

Miriam Frank began her career as a professor in Detroit who launched women's studies at the community college level in the 1970s. She worked with the National Endowment for the Humanities to bring discussions and cultural events to union halls and community centers. She moved to New York to teach at New York University in the 1980s.

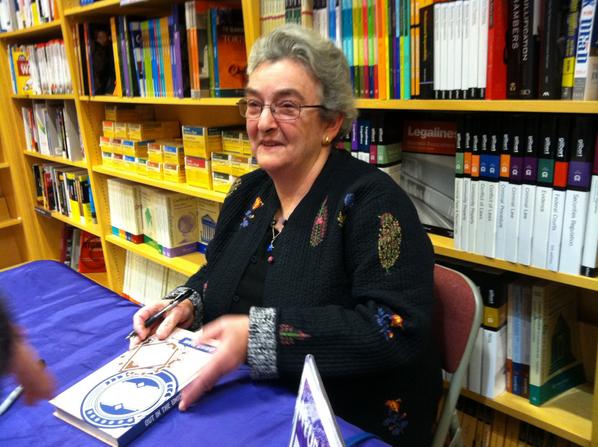

In 1995, she began work on Out in the Union: A Labor History of Queer America (2014), in which she collected oral histories from LGBTQ union activists, many of whom spoke to her at great risk to their personal safety and professional life. A decade later, the work was published and the voices of the activists she captured gave human shape to the intersection between the rights of working people and the rights of the LGBTQ community.

In 2015, she was interviewed by Katherine Turk. Frank spoke about the need for her research:

The field of LGBTQ history includes many studies of queer working-class communities but very few investigations of the actual work lives of queer working-class people in those communities. Traditional labor history considers the everyday lives of working-class people at their jobs in terms of unionization, job mobility, and racial, ethnic and gender segmentation in the workforce. Queer workers and queer issues have not been a topic.

She spoke of the relevance of those workers' words today:

The U.S. labor movement has a great history of strong political coalitions that have pressed for reform on economic and social problems. I wanted readers to consider how LGBTQ trade unionists developed alliances to apply their organizations’ principles and resources to queer union members’ economic status, basic civil rights, and workplace cultures. The successful LGBTQ coalitions that first emerged in the 1970s continue today, influencing collective bargaining priorities, community organizing, regional politics, and trade union ethics.

She described where the movements for labor and LGBTQ rights first started to collaborate:

But as gay liberation entered the political mainstream during the mid-1970s the strategy shifted from radical confrontation to a lesbian/gay civil rights agenda. Two issues emerged, both of them popular and possibly winnable: legal sanctions to halt sexual orientation discrimination and legalization of domestic partnerships. Anti-discrimination policies were included in unions’ constitutions in the early 1970s and the first collective bargaining agreement to protect domestic partners was ratified in 1982. Lesbian and gay advocates in the labor movement based their claims on union principles as old as the labor movement itself—an injury to one is the concern of all.

She explained how being LGBTQ union members were able to overcome the prejudice against them in unions:

From my interviews I have consistently found evidence of LGBTQ union members supporting one another in organizational decisions and working out their differences in frank dialogue. At best that openness flows from the union hall to the workplace and back again. LGBTQ union members who have come out have usually found fair-minded allies among straight and cisgendered co-workers: on the job and in their organizations

Often what sealed that respect was the willingness of LGBTQ activists to join in the projects of their unions. Everyday tasks, focused planning, and casual conversations gave people paths for productive collaboration. Queer people were seen less as outsiders and more as compatible volunteers; the energies of new activists lightened everyone’s loads.